(Note: As explained here, this is a draft of a chapter from an upcoming book on vanquishing financial problems once and for all. Part 1 provided an overview of the structural unfairness in the system that makes extreme wealth inequality inevitable, and covered how that unfairness is implemented through money creation by banks and taxation.)

Money that is Loaned into Existence

Over the first three quarters of the 20th Century, the world’s monetary system was incrementally changed from a system where most money was either gold or silver—or was a certificate backed by one of those—to a system in which almost all money was loaned into existence by those with a government-granted license to create such money, primarily central and commercial banks. These banks do not simply create the money, they grant access to that new money by lending it. This means that, other than coinage and physical cash, which are a very small portion of the world’s money supply, all money is debt, that is, it must be paid back by the borrower with interest.

Most people do not think of their money as debt. They feel that, if they have a bank account, their money is stored in a bank. They do not think that they have loaned that money to the bank, but that is the truth. The bank now owes the person money, plus perhaps some interest on that money. Almost all accounts for which depositors receive a paper or electronic statement involve money that has been loaned to a financial institution.

This reality has created severe problems:

First, a significant portion of the price people pay for anything is interest expense. Let’s say a person buys a bicycle. Many businesses were involved in creating that bicycle. A bulk shipping company transports iron ore from a mining company to a steel mill that supplies steel to a bicycle company that shapes the steel and then paints it with paint from a paint company that has its own suppliers of raw materials from which it makes the paint. Another shipper ships rubber from a plantation to a company that makes the tires and a trucking company hauls the tires to the bicycle plant. The finished bicycle, with many parts attached and provided by yet another set of companies, is shipped to a wholesaler who ships it to a retailer. Each of these many companies is using energy in the form of transport fuels and electricity supplied by an energy company that also has its suppliers of raw materials that were mined, shipped, and so forth.

Most or all of these participating businesses are likely to have loans on which they pay interest. People who have studied this process, such as Monneta.org, say that on average, 30% of the price of any consumer product is due to interest payments made all along the supply chain.

Furthermore, all of those businesses used infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and port facilities built by government projects that are often financed by bonds, that is, by borrowing by the government. Monneta.org has studied this process and determined that the cost of government infrastructure projects would be cut by 40% if there were no interest to be paid on the funds for the project. Thus, much of what people pay in taxes goes to cover interest expense.

This 30% of every consumer product and 40% of every government infrastructure project for interest payments are a massive burden on people, on the society as a whole. (Add this interest payment burden to people’s tax burden and it is no wonder that so many people are struggling financially!)

Next, if everyone is paying so much interest, who is collecting all that money? Who benefits? Clearly, the lenders, that is, banks and those with sufficient means to lend money. Monneta.org takes its statistical analysis of this interest expense phenomena further and shows that 60% of all interest payments concentrate in the accounts of 10% of the populace. They show that the worst of the burden falls on the middle class, which pays a lot of the interest flow on purchased products and through taxes and yet collects relatively little of the interest flow compared with the wealthiest 10% of the population.

Monneta.org has a clear, concise 7-minute video on this topic called A flaw in the monetary system? about interest expenses, the concentration of wealth, and the gargantuan expansion of financial assets entirely out of proportion with the real economy:

Thus we see another major structural unfairness built into the system: money loaned into existence burdens the entire society for the benefit of those who can create money from nothing and those with the greatest amount of money to lend.

Money Designed to Lose Purchasing Power

As we have seen, when money is loaned into existence, there must always be more of it in circulation to pay back the principal plus the interest on the loan. Thus, central banks see it as part of their task to make sure that the supply of money in the society is ever growing to support an ever-growing economy. They publicly state their goal of keeping inflation in the general level of prices at 2% or 3% per year and they do their best to make sure that enough new money gets created to support that increase in prices. They do this to avoid the dreaded-by-them deflation during which there is a more or less widespread difficulty in the repayment of loans plus interest and, instead of money getting created and increasing, loan defaults lead to money simply disappearing from the ledgers of lenders, so the supply of money shrinks. During such periods, the central banks work even harder to make sure that new money gets created. Thus, they seek to have money creation occurring in both good economic times and bad.

But what is the effect on people of having the general level of prices increase 2% to 3% per year? To put it in Dollars, in the US, during a period that the authorities say is a period of relatively low inflation of prices, it takes a $1.46 in 2015 to buy what a person could buy for $1.00 in the year 2000. And this is using US government statistics that are designed to understate inflation, so the truth is very likely worse than that.

What is the effect of this inflation on people? First, it discourages saving and encourages spending. Many realize that if they simply save money, that this price inflation inexorably erodes the purchasing power of their savings. Second, it encourages accumulation of debt. People realize that they can get a loan now and pay it back later with cheapened money. Third, it pressures people to put their money into investments or speculations that they hope will provide a return that is greater than general price inflation. Thus they enter the world of risk assets: speculation in stocks, bonds, currencies, commodities, real estate, and so forth.

This is where the problem of dishonest money arises. Some call for a return to honest money, and by this they generally mean money that is gold or silver, or is backed by one of those. People generally understand that money is useful because it is a medium of exchange and a store of value. The dishonest part arises because of this inexorable loss of purchasing power due to intentional inflation. This puts the honesty of the store of value aspect of paper/electronic money in question because, in the long run, paper/electronic currency is a very poor store of value. In addition, historically, almost all such currencies have lost all of their value, disappearing entirely or being replaced by a new version of the currency that removes a few zeroes from the old currency, that is, 1,000 of the old currency is replaced by 1 of the new currency.

Perhaps the best definition of honest money is money that does not purport to be something that it is not. (For a discussion, see this.) Paper money that is not backed by anything tangible has proven to be an excellent medium of exchange, but a very poor store of value. This will be discussed in more detail in a future post. For our purposes here, what we see is a structure that encourages people to spend now and discourages the independence and security brought about by a person having some savings; that encourages them to take on debt that creates more interest payment flows for lenders; and that encourages entry into financial speculation that inevitably enriches the Wall Streets of the world.

Government Borrowing

The once flourishing and powerful Mesopotamian, Roman and Bourbon dynasties, as well as the British empire, ultimately lost their great economic vigor due to the inability to prosper under crushing debt levels.

—Van R. Hoisington and Lacy H. Hunt summarizing works by David Hume and Niall Ferguson

Most governments around the world are in a simple and intractable predicament: they have made promises they can’t keep, they continually borrow more money to try to meet those promises, and if they break those promises, they are thrown out of power.

Let’s say a government decides it needs a fire department and that their budget allows them to hire 15 firefighters. Part of the compensation for these firefighters is the promise of a pension and healthcare for their retirement years. When these 15 firefighters retire, of course a few will die, but let’s say that 12 of them collect their pension for many years. Now the city must hire 15 new firefighters and they are paying 27 firefighters instead of 15. People live much longer now. With retirement cycles, they may end up paying 30 or more firefighters, some active, some retired, with pensions indexed to cost-of-living increases and with the price of healthcare benefits accelerating faster than the government’s tax receipts for all 30 of the firefighters and their families. So the current cost for firefighters now dwarfs that original budget. It has likely increased several-fold.

Now, add to this small example soldiers, police, school teachers, garbage collectors, administrators, tax collectors, secretaries, spies, building inspectors, diplomats, jailers, judges, clerks, elected officials, border guards, road builders, attorneys, programmers, researchers…you get the picture.

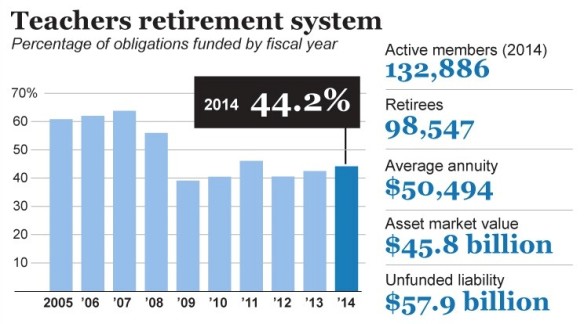

Here is a chart from the Wall Street Journal demonstrating this pension problem from just one of the states of the USA, and just for schoolteachers:

This state has 132,866 active teachers and 98,547 retired teachers. They have assets of $45.8 billion to meet retirement payments, but that is only 44% of what they really need, that is, they are $57.9 billion short. This is called the unfunded liability, that is, promises have been made but they do not have sufficient money to meet those promises. This example, from just one of fifty US states and just for school teachers, gives an indication of the magnitude of the pension shortfall faced globally by governments.

Some say that a key factor in the demise of the Roman Empire was pension promises to soldiers: things worked well while military campaigns brought home the plunder of war, but when the flow of plunder subsided and the number of pensioner-soldiers increased, the massive amounts owed led to payment in severely debased Roman coinage, where base metals were substituted for precious metals, the money-printing technique of those times. To keep their pension payments coming, Roman soldiers sometimes sacked a city to make their point.

It is essential to understand the nature of borrowing: it pulls forward future spending into the present. It allows a person to buy now something for which they have not yet earned the money. But the need to pay that bill in the future, when the money is finally earned, often depresses future spending. When a person has debts, there is usually a payment due every month that is added to the burden of their current expenses. As debt builds up, the person might not be able to spend as much as they wish on current needs and wants. When debt builds up for a society, it can have an increasingly depressing effect on the entire economy. Too much money has to be spent to pay for expenditures from years ago. We are all observing this now across most of the world, with economies groaning under their massive debt burdens.

While government borrowing began to support war and still does, currently it is often justified like this: “We will borrow money now to pay for infrastructure—roads, bridges, and schools, for example—that will be a benefit over decades. By borrowing to pay the cost over 30 years, we spread that cost to the many taxpayers who will benefit from these investments over those next 30 years.” While this has some logic to it, the reality is that infrastructure spending is now only a small portion of the spending of most governments. Most government borrowing now supports current consumption and huge standing bureaucracies.

This distinction is crucial. When a business borrows money to buy equipment that it can use to increase production, then the plan is that the use of that equipment increases company income so that paying the loan plus interest is easy, hopefully with more money left over for profits. Most consider this to be productive debt. But if that same business borrows money to pay rent, utilities, and salaries, how does that present spending produce the future income needed to repay the debt? The same applies to individuals. Financing a car can make sense for people: perhaps it allows them to travel to their job where future income will pay the auto loan plus interest. But when they are borrowing for current rent, food, utilities, vacations, and so forth, the debt tends to build up and, in the future, they must add the cost of paying the debt to then-current costs for rent, food, and utilities.

Borrowing for current consumption, except to cover an emergency that can easily be determined as short-term in nature, is a losing game. The debt for today’s expenses piles up as more debt is added for tomorrow’s expenses. When the amount of debt and interest payments overwhelm the borrower, they are bankrupt, that is, there is no way they can pay back their loans.

Most world governments are in this situation today. Their debt load from the past pressures their ability to spend in the present. And there is no conceivable way they can repay their debts. Yet people keep loaning them money as if nations never go bankrupt, never default on their debt. Here is a chart from The Economist showing country debt defaults from 1800 through 2014. And this chart only shows those countries that have defaulted at least four times, the rest are not shown. Note that the list includes supposed financial stalwarts like Germany:

(Chart source, from The Economist.)

This situation is unjust on multiple counts:

- When countries are unable to repay their loans, it is often a disaster for the regular people of the country. Rich people typically have ways to relocate and shelter their resources, but these methods are unavailable or unknown to the middle and lower financial classes. Essential products and services often become unavailable, leading to hunger and severe medical problems. People’s life savings are often wiped out by bank collapses and/or currency collapses in which multiple zeroes are lopped off the old currency as it is replaced with a new currency. The suffering in recent years of people in Argentina and Greece demonstrates these problems.

- Countries are borrowing with no intention to fully repay the loans. We see overly-indebted countries struggling to create inflation so that they can repay current loans in future currency that is far less valuable, in other words, they borrow today and hope to pay the loans back in cheapened currency.

- Countries are saying to their children and unborn citizens: we want our benefits now and we want you to pay for them. People who claim to want to create a great legacy and life for their children and grandchildren think nothing of lobbying the government to keep and increase their personal benefits which that government clearly cannot afford. Spain, Austria, France, Japan, the UK, Canada, and the Czech Republic have all sold 50-year bonds. Mexico has sold 100-year bonds. These bonds finance current consumption and the taxpayers 50 to 100 years in the future are expected to pay for that current consumption.

- As if the preceding sins are not enough, perhaps the greatest immorality is the one that is hidden from most people: interest payments on all this debt go mainly to those who are already financially secure, paid for by those who are much less so. Monneta.org has shown only those who are financially in the top 10% are net beneficiaries (they receive more interest payments than they pay out in interest and taxes) from all this interest expense. And the amounts of interest are huge. From 1988 through 2014, the US federal government, for example, has paid $9.4 Trillion in interest. With the current national debt at $18 Trillion (in early 2015), clearly a huge portion of the accumulated national debt is due to interest payments. Since the few benefit from these interest payments as the rest of the populace pays the bill, once again we see the intentional structural unfairness that pervades the entire financial system.

Governments borrowing money into existence

Almost every government today does not simply have its Treasury Department or Finance Ministry create its national currency, it grants that concession to its central bank, which lends that money to banks or the government itself. Thus, as with commercial banks, the money is loaned into existence and interest must be paid. In some nations, the central bank is a branch of the government, in others it is a private bank. Either way, the money is loaned into existence, saddling the entire society with massive debt that requires interest payments. Were the government to either back its money with gold or silver, or to simply create that money without borrowing it, the taxpayers of nations would not be saddled with today’s huge interest payment burden.

Why is it done this way? Well, what is the job of the central bank? Since it can create infinite amounts of money if needed, it is considered the lender of last resort when there is a financial panic. And whom does it save during financial panics? Primarily banks. So the real job of this central bank is to protect commercial banks, to assure that their money creation cartel remains intact.

And what is the first resort when a nation gets into trouble because its debt load has become too large? More loans! This is always the solution from international banking organizations such as the International Monetary Fund. So the fire of too much debt is fought with additional fire, placing an even larger debt burden on the already over-burdened taxpayers of a country, who now owe even more money to bankers. If an economically-troubled nation does not cooperate with these measures to saddle them with even more debt, the international banking community threatens them with various types of monetary exile—such as lack of access to markets to export their own products or to import essential products not produced in that country—that will turn their economic situation from a serious problem into a humanitarian disaster.

In this manner, all nations and their people become debt slaves. This is a key element in the very well-devised plan for structural unfairness in the financial system.

There is more in Part 3.

Pingback: The Current System is PURPOSE-BUILT for Extreme Wealth Disparity, Draft Part 1 | Thundering Heard

Pingback: The Current System is PURPOSE-BUILT for Extreme Wealth Disparity, Draft Part 3 | Thundering Heard